Finding the Contemporary among the Ancients

by Ted Sandling, Presenter of The Contemporary Art World: Theory and Structure and Programme Director of Online Courses, Christie’s Education

Ben Street has taught at Christie’s Education for many years. He specialises in contemporary art, a subject he often publishes on, and is currently completing a PhD on Philip Guston. Perhaps more notably still, Ben cameoed in LCD Soundsystem’s video for their seminal hit, Daft Punk is Playing at my House – although he’s not recognisable. He had a cardboard box on his head.

Ben’s a long-time collaborator with Jasper Sharp, founder of Phileas, the Austrian art fund that helps get Austrian artists a global audience. Phileas trebled the participation of Austrian artists at international biennials since Jasper founded it in 2014 – the same year he curated the Austrian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Ben and Jasper have a huge amount of experience working with and thinking about contemporary art and artists, so bringing them back together to film a discussion for the Christie’s Education online course The Contemporary Art World: Theory and Structure seemed too good an opportunity to miss.

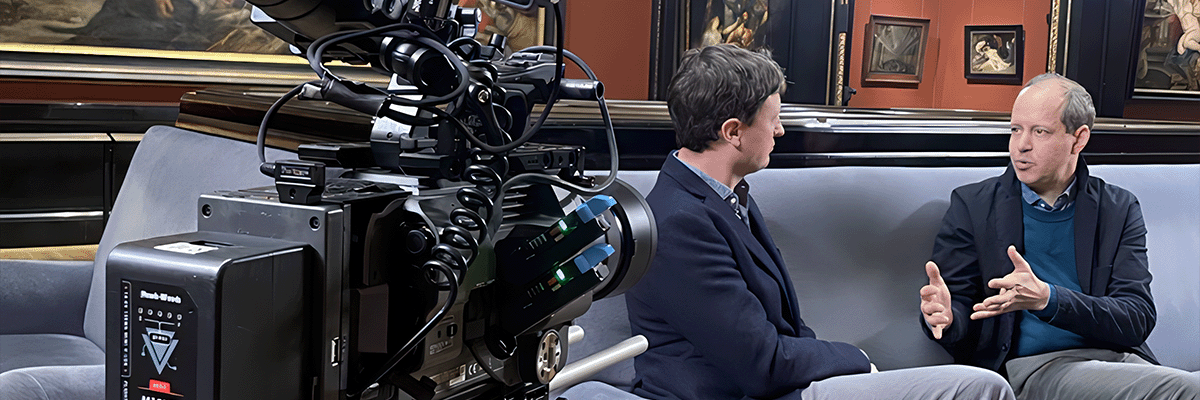

We met in Room XIV of the vastly ornate 19th century Kunsthistorisches Museum on Maria-Theresien-Platz, Vienna. It’s an unusual room to film a feature about contemporary art, because it’s filled with almost overwhelmingly large paintings by Rubens. Indeed, the collections of the Kunsthistorisches Museum (literally, Art History Museum) date back millennia, but they stop in 1800. Jasper said it’s, ‘missing two hundred and twenty-three years of art history. Every year that we live, we move one year further away from this collection. The collection doesn’t move with us.’

So why meet here? Why film a conversation about contemporary art in the shadow of Rubens’ 4.5 metre tall Assumption? Because for over ten years, this museum was Jasper’s home. Not as a curator of the old masters or antiquities – but especially to introduce art of more recent times into the museum. He felt you had to be either ‘respectfully radical or radically respectful. But not just radical, provoking without something beneath it. And if you’re just respectful then don’t even bother coming.’

Ben and Jasper worked together on the Vienna Kunsthistorisches Museum’s The Shape of Time exhibition in 2018, which created partnerships between works of contemporary art and objects in the Museum’s collection. But before that, Jasper had introduced other ways of bringing contemporary art to the Museum. Artist talks were one: ‘Get an artist here from somewhere in the world [Jeff Koons, Nan Goldin, many others]. Meet all the curators, all the conservators, walk around the museum. Go into the storage, see what’s not on display and on the last evening, sit on a stage and say, ‘Just tell us about everything you’ve seen for the last few days.’’ The talks were always revealing.

He'd also invited artists to come and curate their own exhibition. The first was Ed Ruscha, who found exploring the collections ‘totally depressing’.

‘Why?’ asked Jasper.

‘I’ve just seen every idea I’ve ever had in my life on the walls of this museum this morning. Every idea.’ And when Jasper said that would probably apply for every artist, Ruscha found a way through, ‘It reminds me of this line from Mark Twain: The ancients stole all of our great ideas.’ And that became the title for the show: The Ancients Stole All Our Great Ideas.

Perhaps the biggest show Jasper worked on was curated from the Museum’s storage by Wes Anderson and his wife, Juman Malouf. That not only saw huge numbers of attendees in Vienna, but when it toured to the Prada Foundation in Milan it became the most successful exhibition in their history. And then came Jasper and Ben’s collaboration, The Shape of Time.

The idea for the exhibition came from Ben’s writings about encounters between objects. ‘I became very fascinated by this piece by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, from 1991’ Ben said. ‘It’s a pair of ordinary wall clocks, deliberately very banal. They’re moving together and then at a certain point one of them will stop moving. And I thought it was such a beautiful metaphor, it’s a piece of poetry that happens to be in physical form, about time and togetherness and relationships.’

Ben said that this is a fundamental idea in other art works; in particular he was taken by a painting by Piero della Francesca in the Uffizi, the Diptych of Federico da Montefeltro and Battista Sforza of 1473-75. The Duke and his wife are in profile on two separate panels, and they’re looking at each other, together but also apart. And in Ben’s imagined pairing, the Felix Gonzalez-Torres object helped him to understand what was really at stake in the Piero painting. ‘Those two next to each other create a third thought. The idea really comes from Marcel Duchamp, ‘creating a new thought for that object.’’

‘It’s a private encounter,’ said Jasper. ‘It’s a very intimate moment, in the middle of all this,’ and here he indicates the vastness of the Kunsthistorisches Museum. They put together a Rothko and a Rembrandt, a Cezanne and a classical statue, Peter Doig and Brueghel. Kerry James Marshall reworked Susanna and the Elders by Tintoretto. The exhibition was up for three months: eighteen pairings in all (Jasper: ‘I think in the end maybe fifteen worked.’).

In the end it comes down to Ben and music again. ‘You’re a great playlist guy,’ Jasper says. Ben waits to see where this is going. ‘And what a playlist is, is taking a song off the album with which it was constructed. This exhibition? Putting it on a playlist. You’re not damaging that song forever, because it still exists. And any exhibitions that do that are for three months. And three months over the course of centuries? It’s the length of a song. It’s about giving them different neighbours. You’re going to meet friends that you live in the same apartment block with, that you’ve never met before. Let’s see how you get on!’

Learn more and register for The Contemporary Art World: Theory and Structure